Indigenous Youth complete first descent of undammed Klamath River from source to sea

43-year-old Roderick Randall is being held in Texas on federal charges related to providing false information to federal law enforcement officers.

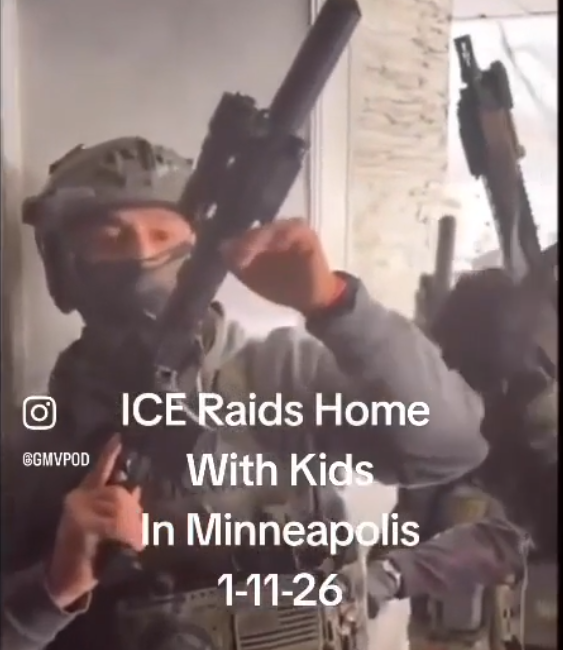

What if there are no consequences for blatant and repeated violations of the Fourth Amendment?

Meetings and events in Elk Grove - Restaurant Week is Coming!

The event was organized after the killing of an American Citizen by an ICE agent in Minneapolis